Tomcats, L1011s, Boeing 777s. Afghanistan combat missions with airborne refueling. Blind Landings in U.S. Aviation. Car-quals for USMC F4U-5 pilots.

Copyright 2015 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

Context: Instrument Flight, vs.Flight

Contact Author Franklyn E.Dailey Jr.

My "hands-on" activity as PPC in the pilot's seat of a Navy patrol aircraft came to an end in 1962. From that year on, my understanding of both commercial and military aviation has come from reading, from flying as a passenger, and from discussions with those who have been direct participants in aviation progress in the United States.

Before the defeat of Germany in World War II, the Luftwaffe had introduced both jet fighters and rocket plane interceptors into combat. Too late to change the outcome of the war in Europe, Germany nevertheless pioneered the operational jet age. England was not far behind with the U.S. a close third. Both the United States and Great Britain had test versions of jet aircraft well along in development programs by V-E day.

My own first recollection of jets in the U.S. was the Lockheed Shooting Star, a single-seat jet fighter plane. The squadron I reported to in 1951 received a two-seat trainer version (TV-2) of this aircraft to begin checking out our "middle-aged" (anyone over 30) pilots. At this time, the real Navy fighter "jocks," with their new steam catapaults and canted flight decks (both of which were British ideas) became operational on carriers then supporting both propeller and jet aircraft. In the multi-engine sector, I can recall USAAF pilots at Long Beach airport making touch-and-go landings about 1950 in a twin jet bomber about the size of the World War II B-25 Mitchell. Those early twin-jets took a lot of runway for takeoff and had to stay pretty close to an airport. Fuel consumption rates were high and fuel capacities were low to keep weight down so that these planes of limited takeoff thrust could get off the ground. JATO, for Jet Assisted Take Off was an early application of jets in a supporting role. Afterburners were developed to give take-off thrust assists in the launch of practical military jet aircraft. I can recall successive afterburner "booms" emanating from Westover Field, Massachusetts, near my home, when a squadron of F-102 or F-106 aircraft would be scrambled. Those reminders of the Cold War took place before Westover lost its fighters and its B-52 bombers and became a reserve base with C-5 transport aircraft. In the early days of operational jet squadrons in the military, "tail pipe temperature" was a required part of the jet powered aircraft check off list. If it was too high, engine thrust could be lowered and takeoff distance lengthened. More importantly, the hot metal could develop an unsafe condition that could work its way forward toward the heart of the powerplant. So, flights would be rescheduled for hours when the tail pipe temperature readings would be lower.

One of my memories of early commercial jet flight was a United Airlines Boeing 707, a "short version," making its maiden flight about 1956 or 1957 from San Francisco to San Diego. This plane landed into a beautiful Lindbergh Field sunset, letting down very carefully over the El Cortez Hotel. In the 1950s, the Air Force introduced the B-47, a range-starved nuclear delivery platform, quickly superseded, I am sure to an Air Force pilot's great pleasure, by the B-52 of enduring operational life. British aviation gave us the four-jet Comet. After a number of incidents and fatal accidents, this aircraft was quickly retired from service. Travelers connecting through O'Hare recall one parked there, abandoned in effect, too costly to fix and fly to a decent burial in England. Her four jets were faired into the wings, as were the Navy's P-6, an ill-fated four jet seaplane built by Martin in Baltimore. Both of the XP-6s crashed and the effort to create a military seaplane with jet power ended forever.

The Navy tried twin-jet aircraft to deliver fat nuclear warheads from aircraft carriers, with the AJ being an aircraft of short operational life and quickly forgettable capabilities. Douglas got the Navy successfully into multi-engine jets for carrier-based nuclear delivery requirements. The Navy added two jets to the two Wright 3350 propeller engines on the P2V to create the P2V-5F series that extended the useful life of that successful patrol aircraft. In my own flights in that aircraft, we always used the two jets to shorten our takeoff runs. Jet-prop aircraft also came into the inventory. For civil aviation and for short haul airlines these have maintained some performance advantages. But, by and large the "pure-jet" has won the day.

Power plant development for aircraft propulsion is a dramatic story. The liquid cooled in-line engines gave way to the air-cooled radial engines. Then came turbines, in both the pure jet version and the prop-jet.

The jet engine, as first as used in the military fighter aircraft, forced the domestic air traffic control system to incorporate important improvements in instrument flight procedures. The early jets were fuel-limited. The fuel per mile efficiencies eventually became very good but the U.S. Air Force made in flight refueling a standard practice for longer flights and the Navy followed suit. All-weather performance for jet fighters became a requirement, not something a pilot needed only when he got caught in instrument flight conditions. So, the military developers of air traffic control procedures, with the assistance of expertise in the ranks of civil air traffic control operators, pioneered faster penetration of destination weather systems, with steeper, straight in approaches of shorter duration, all contributing to simpler and safer instrument landings.

Two F8F "Bearcat" chase planes shepherd an F6F-5K Hellcat drone near NAS Chincoteague about 1952

I do not want Illustration 9 from my book on page 65 of "The Triumph of Instrument Flight," reproduced above, with its Grumman fighter planes, to lead the reader to believe that I was a part of any "new age" of flight. That photo actually represents the highpoint for U.S. Navy World War II high performance fighter aircraft. These were fast prop planes. They had good flight control instrumentation but had limited radio receiver options. I was flying the F8F-2 in the center of the formation in support of drone missions to give the USS Mississippi's Terrier missile batteries some operational target experience. The F6F-5K, a modified Hellcat, had a Bendix autopilot and receivers for remote commands so that it could be controlled from takeoff through landing from chase planes or ground control. We also readied the Hellcat to be flown off carriers with heavy bomb loads into the shore hugging railroad tunnels of North Korea. The photo was taken on an operational drone mission launched by Navy Squadron VX-2 from NAS Chincoteague VA about 1952.

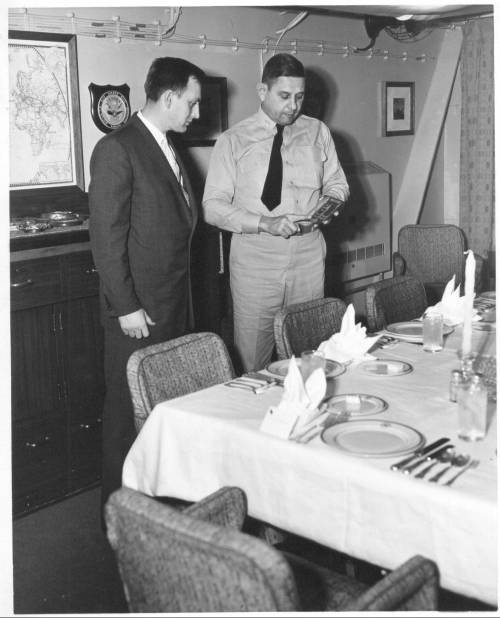

The photo above shows author Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.with RAdm Reynold D. Hogle aboard USS Leyte CVS-32 in November 1958. Dailey was aboard to observe carrier qualification of a Marine Squadron with new F4U-5 aircraft. It hardly seems possible that the Navy was car-qualifying these pilots so late in the life of Corsairs. When the USMC wanted to form new units they did it with bare essential personnel records with little regard to the prior experience of its pilots. And, this Corsair model had a nasty habit of engine momentarily conking out when the pilot had to take a waveoff. I was standing next to the island on the Leyte next to the photographer who was required to photo op every landing or attempted landing. He called me over and said, "Commander Dailey, I have to stand here but my advice for you would be to get over there behind something substantial." The Marines had a great week; all pilots qualified and there were no accidents or even incidents. A few hairy go-rounds maybe. The Admiral was a great host and the ship was beautifully handled.

Many of the World War II fighter planes were not instrument-qualified, mainly because they had no second option in case of primary radio failure and no backup flight systems. I flew some of these aircraft under instrument conditions only when I unexpectedly encountered instrument conditions. In some ferry flights, to move a plane to another base, I went around weather and in one northern Florida weather front near Jacksonville, practically flat hatted (flew lower than allowed Visual Flight Rule minimums) to avoid clouds in order to reach NAS Sanford, Florida. The climb out at Niagara Falls when returning an F8F from a hurricane evacuation involved a solid 10,000 feet of overcast. I did not fear it, knowing from my aerology briefing and from an incoming pilot that the "tops" were clearly marked at about 10,000 feet.

The jet fighter pilots that matriculated with the new technology into the era of all-weather fighter aircraft marked a new breed of military pilots. These men and women made contributions not only to execute missions requiring penetration into instrument weather, but their new destination-airport weather penetration techniques, with time-abbreviated approach and letdown procedures, have benefited all aviation.

I hope to have made it clear that a central theme of this story is that the U.S. has set a notable mark in civil aviation. Technology has been an important factor, though I have hardly addressed that subject. (From response to an earlier book of mine, I also realize that some will feel that this story contains far too much technology.) The instructor personnel involved at the thousands of civilian airfields, and the training they give and promote, the young pilots they have graduated and the Aircraft and Engineering (A&E) licenses that have been earned, have made a variety of aviation careers attractive and challenging. The flight simulators used by the airlines have made an enormous contribution. These systems are a huge advance from the Link Trainers we used in the 1940s. I salute the Fixed Base Operators (FBOs), many of whom struggle to make ends meet and keep a facility going. They deserve recognition.

I recognize and salute commercial airlines. I am proud that I am now in a modest way, a member of an airline family. One of my sons has made American Airlines his career, not as a pilot, but as reservations agent, ticket counter agent, ramp agent, and baggage agent. His wife, now a teacher, has been an American Airlines overseas boarding agent, and with her gift of the Spanish language, was chosen to help open South American terminals for her airline. Another son has a wife who is a stewardess on American Airlines' business-building South American runs. She finds time to be mother to two children. Another son's wife has just retired from more than 30 years of flying as a stewardess for Delta Airlines. Her recognition of the value of Robert Mudge's story of Northeast Airlines got me launched on this story.

I have learned from my considerable experience as a passenger, and from all of these next-generation family alliances, these loving alliances, that the success of an airline in 2010 is built on employee tension, from the cockpit to the tarmac.

Airlines work hard to get out on time, as carefully loaded as possible and as full as possible of law-abiding, paying, passengers that can be attracted to its services. I have learned from my own ability to see what is happening in the scenes and behind the scenes when I have been an airline passenger, for one period a frequent passenger, that every employee of a scheduled airline in this new millennium is a Lifeguard at Shark Beach. In today's global environment, it would not work any other way. There is no easy job in the airline business. We passengers expect a lot and we get a lot. Safety must take precedence and we enjoy unprecedented safety in flight. The folks I have written about in the 1920s, 30s and 40s set us on the safety course and we need to recall them with gratitude. But, there are people who do not like us. Tension produces performance and our society has demanded performance. Still, I have reflected on this and worry about it and do not have any idea how we might relieve that tension and still achieve the results we demand.

I am proud of my ACA-170 certificate No. ITL 1352261, dated 09/25/56. It was issued by The Department of Commerce, Civil Aeronautics Administration, signed by the Director Office of Aviation Safety, and it indicates that I have been found to be properly qualified to exercise the privileges of "COMMERCIAL PILOT" with Ratings and Limitations of "AIRPLANE MULTIENGINE LAND INSTRUMENT."

Reading the back of the certificate, I learn that I am in violation of the provision that I notify CAA of a change of address within 30 days. Just now, as I examine that rule, I realize that I have changed addresses more than 20 times since the address I submitted when the application was approved. That address was a fine home out on beautiful East Avenue in Rochester, New York in the Brighton section. My mother had a small apartment at that address. I frequently used it because as a Navy itinerant, my own family lacked a permanent address. That Rochester address has been chewed up into what Rochestarians call, "The Can of Worms," a highway interchange. Progress, you old devil you!

When I was leaving for World War II from the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA, the "trade" school, many called it), my mother and father wrote me letters with small talk about family life back home. I recall specifically, the stories about my (younger) sister, who had begun dating. My parents wrote of the noise of the motorcycle arriving and bringing a young male date to our front door. Those letters often featured an extra paragraph to tell me about the noise of a Harley-Davidson leaving our front door on Faraday Street in 1942 in Rochester, New York, well past the neighbors' evening bedtimes. One of those young men ended up in a P-47 flying out of Britain for the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II. (Sadly, he did not make it back.) I developed this mental connection between motorcycles in peace, and fighter aircraft in war.

I have not held the "yoke" or the "stick" of an aircraft since the mid-60s. When I was a child growing up near the New York Central railroad tracks in western New York State, I could hear the big freight going through every night about 2 a.m. Its steam whistle was a thrill. When the snow got too high even for a utility steam engine's plow during our harsh winters, I would wake up because I did not hear a whistle that night. For the past twenty years, a twin engine plane has come over my home every morning in the 4 a.m. darkness. Those are surely two radial engines, like the twin Beech of yore, and I can hear the pilot "synch-ing" his engines some mornings. In occasional bad weather, I have missed him or her though that plane's on-schedule reliability has been so good that I am sure it made it to Hartford later in the morning. Where did it originate? I had pretty good binaural hearing up to five years ago so I tracked that plane from Portland, Maine. Even on clear nights, it was obviously on the Bradley Field (Hartford, CT) approach that takes most instrument flights over my house. Why was that little plane making the trip so regularly, weekdays and weekends? Well, I can speculate that it was bringing fresh lobster to the elite of Hartford. My pilot friend has been missing for nearly five months now. I miss that plane. It was my last active connection with aviation. Just as with the steam engine pulling that midnight freight, another cycle of my life is complete.

Today, young ladies are fully involved in all aspects of U.S. aviation. I see those confident young girls driving by my home, some now on motorcycles and many sitting high in their SUVs. I am seeing the well spring for a source of future pilots. We will be better off, and they will be better off, when they trade that cell phone for a good pair of earphones embedded in a hard hat.

I worried that I did not have fresh anecdotal material to emphasize these final thoughts. Three e-mails have saved me.(The foregoing was slightly updated in 2010.What comes next is as the pilot wrote it in 2001. I am still in thrall of the accomplishments he relates so matter of factly.)

"28 October 2001

Had a mission tonight that went really well. Sweaty (our girl pilot) was on my wing and she hung in there really well. We went out to the tanker (the first of three times) and it went ok, but three and a half hours later, after the moon had set, it was so friggin dark. We all have our lights off so the bad guys can't see us. To tank we have to take our night vision goggles off, and it takes 20 minutes for your eyes to get used to the dark again. So I came off the goggles and tanked immediately. All I could see was the dark mass of an L1011 and the basket of the drouge we plug into. The air was a little bumpy and there was no horizon. I tried to stare at the basket and fly formation off of that, but I started to get Vertigo. I was in a turn with the tanker but I did not perceive it. I was bouncing around and getting dizzy. It is the hardest thing I have done in a while.

The combat stuff is going well. Our four ship, of two Tomcats and two hornets (I will never capitalize the plastic plane!) was going after stuff...and coming off target we started getting anti aircraft artillery coming up at us. They could hear our jets and were shooting at me. It looked Roman candle balls coming up in streams. I saw on the mountain where it was coming from and rolled in on the site. We got a designation, and I came off and felt a thump under my bird. Now I was pissed. We had good engine readings and the hydraulic system was good, so I was not too worried about the jet. We watched that spot on the ground with our system and when they shot again, we were able to pinpoint where it came from. Next pass they got a thousand pounds of love riding a laser beam shining on their heads. It is strange to say that killing people could be satisfying, but I wanted to cheer. "Oh, so you want to shoot at ME?" The jet was fine for the trip home, and we landed uneventfully, if a night carrier landing with no moon at all can be called uneventful.

I took some pictures the other day, and some from a night strike through my goggles...they are awesome, I just wish they did not limit the field of view so severely. It is like looking through two toilet paper tubes. The countryside is so barren. Nothing but rocks and dirt, and more sand than you can imagine. Who would live there? The river valleys have some agricultural development, but as you go further North it is Grand Canyon like. I would love to go raging around in all the terrain, but it is too dangerous below a certain altitude. We don't go below it.

I don't have much to tell you about except work. Have not been working out so much, and movies are right out. We have our first "Beer Day" coming in about a week. If we are at sea for more than 45 days straight, they give everybody two beers. Somehow, people manage to get more. I might be doing some scrounging.

Trying to take some video of stuff, just to keep records of all the things we do. Ready room antics are alive and well, and the pranks are starting. We took Jay's springs out of his bed and hid them in another room. This after he tried for weeks to get them in the first place. He was only getting a couple hours of sleep a night because the bars under his mattress made it terribly uncomfortable. Last week he found an unused set in another room and took them. The S-5 guy in charge of beds said he needed them back, and Jay refused. A couple days later some worker bees came in and tried to take them. Jay flipped and kicked them out. So he came in yesterday from a 9 hour mission at like noon and found his springs missing. I thought he was going to have a stroke. He called the S-5 Lt(jg) who had threatened to take them back because he needed them for some visitors coming out to the boat. Jay assumed that this poor guy had taken them back. He was dressing him down with a vengeance, making him say sir every other word. The S-5 guy went and cried to the XO of the ship and our XO had to apologize. (our XO was in on it all along) Jay took it well. I will never forget him coming in and ranting to himself, "They took my springs...I have no springs...hrmph." I think we should start some trouble with the hornet Bubbas...but they don't joke so well. A year ago when we stole the hornet squadron's table that said "single seat forever" and took it to Fallon and put in on the Bombing range. (and shacked it of course) , their Skipper called NCIS (FBI of the Navy). He threatened to press charges...no sense of humor, so we are hesitant to go there again. There really is nothing like being in a tightly knit organization. Even more so when you are living day to day, trying to make the most of a bad situation.

Hope you are taking care. I am looking forward to getting home and saying hello in person. Chad"

"02 November 2001

Subject: A Quick Note

Chad: We wanted to say hello and tell you that we saw your ship on Channel 1 news. We saw some of your shipmates. We were able to get an idea of how you live. We watch Channel 1 news daily. Channel 1 is a news program produced for students and teachers. The reporter on the ship was Seth Doane. He reported that the ship is on an inverted schedule. Are you on the schedule eating breakfast at 6:00 a.m.? He interviewed Tim Parker- he was a flight deck person, Jason Cusak and Scott Sally as seaman, Dustin Osborne as the chef and Jerelle Harthy who recycles all the trash.

We feel sorry for you because we saw how small your bunk is. We hope that you be careful when you get out of bed and hit your head. We also saw one of your gyms where you work out. Lindsay wants to know if you have a curfew? We saw a night landing and the cable you have to snag when you stop. It was cool to see. Leeza wants to know if the quick stop jerks you forward? Alisha would like to know if it's a quick trip to your target?

Do you have a maximum time to fly? Adam wants to know what you do if you have to go to the bathroom while you are flying? We wanted to say HAPPY HALLOWEEN and tell you the world series is tied 2-2 Yankees to Diamondbacks."

"Re: A Quick Note

Hi guys,

Things have been very busy as the operations have stepped up. Our flights are lasting over 7 hours. Imagine strapping yourself to a (hard) seat, one that sits you straight up, for that long. Getting out of the jet after landing yesterday, I almost fell off the ladder my legs were so stiff. It made me wish I was 14 again. I had loosened my lap belts to stretch out a bit and did not tighten them back up. When we came in and snagged the wire, I was thrown forward into the instrument panel. I smacked both my knees on the gauges...OUCH! We have been taking off around midnight, then flying through Pakistan to the airborne tanker where we get gas. Our plane has a probe that we can extend. The tanker has a basket that is shaped like a badminton birdee. It is attached to a hose coming out the back of the tanker, and we fly up behind it and carefully plug our probe into the basket. Then they turn on the pumps and we can take fuel from the big tankers. We tank twice going in and twice coming out of Afghanistan.

If we are flying too much, the Skipper has to give us a waiver to allow us to fly more. The limit is 65 hours in a month. I have gotten 45 hours in the last two weeks, so I will need one. With the long missions going to the bathroom has become an issue. We carry a specially made ziplock bag. It has a powder in it, and we use those to go. It is hard to take care of that and fly at the same time, but sometimes you HAVE to go.

Our squadron is split between Yankees fans and Diamondback fans. Since we are called the Diamondbacks too, I have been rooting for them, but I don't really care who wins. I wish I could send the videos of the strikes we have been doing, but they are still secret. I will put a bunch of clips that I have taken together, and send it to you when I get a chance. Thanks for the support, and Hope your Halloween was fun.

Take care,

Chad"

I have endeavored in the early chapters of this story to present a theme that military aviation and civilian aviation have been very important to each other, almost co-dependent, during the formative days of U.S. aviation in the early part of the 20th century. Gradually, during the last 50 years of the 20th century, the bond has loosened. Each of these components of aviation is now quite self-sufficient. Yes, the civil airlines are still happy to see a healthy cadre of trained military pilots knocking at their doors for openings in pilot ranks. But we are not likely to again see contract civilian pilots manning military planes to establish new air routes needed for military requirements. Nor is it likely that civil and commercial pilots would be needed again to man hundreds of new military pilot training bases sprouting up all over our country.

The later chapters have centered on events in which I have in some way participated. The contributions to our country of civil airline pilots, Navy pilots and pilots in the Army Air Corps defy measure. It was never a challenge in the writing of this story to make any special effort to look for examples to relate. In telling the story that I wanted to tell, I came upon example after example of the valor, the ingenuity, and the pioneering that both civil aviation and the military air services mean to this country. Watch a Coast Guard helicopter crew on TV as it makes a rescue at sea. That takes proficiency way up the scale.

The comparison between Instrument Landing System-ILS instrument approaches to a landing and the use of Ground Controlled Approaches-GCA for that same purpose illustrates one of the earlier preference differences between civil and military aviation. In the employment of either of these instrument landing aids, the pilot has his hands on the flight controls and is using his gyro horizon and his gyro compass to furnish the essential information needed to keep to a pre-defined flight path. In the GCA approach, a pilot is coached back onto the correct flight path by a human voice stationed near the runway on the ground. With ILS, the pilot is coached back to the correct flight path by reference to another instrument on his panel that combines information on the plane's deviation in azimuth and elevation from the correct flight path.

Let me go back to the Aleutian flying I did in 1946-48 to illustrate the value of GCA to military pilots at airfields before ILS existed. The two principal airfields for Navy pilots were at Kodiak, Alaska and at Adak, Alaska. Both had low frequency radio range letdowns with approaches coming from the sea. Their main instrument runways headed into steep mountains. When making low frequency radio range approaches at either field, mandatory pullups were required well short of the designated instrument runway if the pilot had not gained visual contact with the airfield during the approach. Both fields had GCA units and thank God for that. On a GCA approach, the pilot turns control of his aircraft heading and altitude over to the short interval vocal commands given by a ground operator (the GCA controller) who can see the plane on special radarscopes. The polished vocal practice, a result of much training, of the ground controller included a requirement that he or she never be silent for any sustained period. The pilot followed the directions of the controller in flying his plane right down to touchdown. The skill of both pilot and GCA controller was to never let the aircraft get very far from the desired position so that corrections were always small. A safe touchdown resulted from a collaborative effort.

About the middle of my Aleutian tour, in May of 1947, our Privateer aircraft were outfitted with new electronic equipment bearing the designation, SCS-51. Many of the airfields we used were just being equipped with the ground electronics installation necessary for the SCS-51 equipment to work. Known as ILS, for Instrument Landing System, in the commercial airline world, the SCS-51 system provided the pilot with constant glide path and azimuth information in graphic presentations in an instrument display right on his instrument panel. The pilot actually "sees" whether he is high or low from the correct glidepath and right or left of the correct glidepath. It is a very good system and it is used today (2002) in more advanced versions.

The pilot's gyro horizon and gyro compass indicators were vital to the "small correction" concept of a GCA approach. And were just as vital to the "small correction" concept of the ILS approach.

First use of ILS in commercial aviation is credited to Braniff Airways in 1947. Commercial airline, air freight, and corporate aircraft pilots would almost always choose to use the ILS system over GCA, when both were available, because the pilot stays in complete control. When the pilot reaches minimums and cannot see the runway, he or she can execute a "missed approach procedure" and take the plane back to altitude. Commercial pilots believed in their abilities and wanted hands-on control of their aircraft during takeoffs and landings. Commercial pilots, many of whom are ex-military or military reserve pilots, did not minimize the value of GCA and would certainly have used it if required, but their choice was ILS.

World War II military pilots welcomed GCA because it gave them a chance to get back on the ground safely when a low frequency radio range approach or an Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) approach would still leave them up in the clouds. GCA was a life-saving solution that came during the war to some military bases.

There was no SCS-51 in those war years, military or civilian. (In an August 2013 e-mail, included at the bottom of this page, John Turanin points out an official publication that shows my now italicized sentence to be incorrect.)

A GCA endearment was the intimacy of the attention given by a ground controller during the critical period of a pilot's descent to the ground under instrument conditions.

ILS still shares much of the load for instrument weather situations involving low ceiling and low visibility approaches and landings in the United States. ILS is passive, and not only in the sense that the pilot keeps control of the aircraft. With ILS, there is no personnel crew on the ground to be paid and trained and on watch 24 hours a day. For the most part, ILS and related methods have become the standard.

For those readers interested in pursuing further knowledge on how low ceiling, low visibility instrument approaches and landings are handled in 2001a little web searching is a good first step. First, the acronym "GCA" will now fetch such groups as the Green Communities Alliance, Gun Control Alliance and Global Coalition for Africa. One must insert the full "Ground Control Approach" terminology to discover that two full GCA systems are archived at the Wright Patterson Air Force Base Museum.

At their website, www.wpafb.mil/museum , one discovers that the final resting place for two complete GCA sets, one from Keesler AFB, in Mississippi and the other that had been in service at Wright Patterson Field, is the U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson Field.. The Keesler unit remained in service until 1980 and the WPAFB unit until 1978. As improved, after World War II, these units consisted of a search radar system with a 45-mile search radius, a two-way voice radio system, and a precision radar system for use during the final 11-mile final approach to the runway. Those web pages include a brief statement on how this equipment was used. For example, " It-the precision radar-alternately scans in both the vertical and horizontal planes to track the approaching aircraft's line of descent and course. The controller advises the pilot by radio of any changes in glidepath or course needed to accomplish a safe landing." One interesting paragraph cites the Berlin Airlift in 1948-49, in which hundreds of lives were at risk in the air and on the ground, as an indication of GCA's effectiveness, and persuasiveness, while in use.

The insertion of "ILS" into a web search engine leads to that acronym's use by many organizations that are not remotely connected with instrument flight. One result, however, was "Instrument Landing System" and a very helpful website, home.sprynet/~jayschnell/Ils1.htm

This website is copyrighted by Mr. Jerome Gerald Schnedorf III. In a page headed, "Instrument Landing System," Mr. Schnedorf visualizes a precision instrument approach as a child's "slide at the park." He likens the non-precision approach to "a series of steps on a staircase." For the non-precision approach-he cites nine real-world examples from which a pilot might choose - a directional system such as a passive Localizer, or an active system such as an Airport Surveillance Radar - to aid him in bringing his aircraft toward the instrument runway in use on the correct runway heading. During this type of non-precision approach, the pilot lets his aircraft down, say in 500 foot steps, until arriving at some previously defined minimum altitude in the immediate environs of the field. The precision approach systems that Mr. Schnedorf defines are the Instrument Landing System (ILS), the Precision Approach Radar (PAR) and the Microwave Landing System (MLS).

As a direct consequence of putting a draft version of this story on our publisher's website (www.daileyint.com) in November 2001, I was privileged to enter into dialogues with two recently retired airline pilots in early 2002. The results follow:

With his words, "We've come a long way; baby,"

Retired (1997) Delta Airlines Captain Robert E. Mitchell brought retired Navy Captain Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. up to date on "hands-off" landings under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) conditions. In an early chapter, I had written (and have now removed for reasons that will become obvious), "Commercial aviation is not ready in 2002 for this mode of operation." The lines that follow were the summary response of Captain Mitchell on 02/12/2002 to my out-of-date sentence.

"In fact the present generation of aircraft (typified by B-757/767/777) are equipped for just that, and the crews so trained. It is common practice and approved procedure to engage the autopilot/flight director and RNAV (horizontal) and VNAV (vertical) at 1000 feet agl (1000 feet above ground level) after takeoff and not touch anything (including the brakes) until you reverse the engines on roll-out. Normal minimums for these aircraft going into a large airport that is Category III equipped, is just 600 feet runway visual range (no ceiling requirement at all). In essence, you don't see anything except the green centerline lights as you roll out!"

Here is Captain Mitchell's 02/13/2002 follow-up to his summary paragraph:

"Well, that is pretty much what computers have done for instrument flight and approaches in the last 20 years or so. I found as an instructor that getting a student (maybe with as much as 15 - 20 thousand flight hours and no previous experience in the 'glass cockpit airliners') to grasp the concept was no small challenge. You must realize that a lot has probably changed in the years since my (1999) retirement.

"The auto-flight system and controls in the B-757/767/777 aircraft are almost identical. In fact, the FAA issues an ATR rating (Airline Transport Rating) that is common to all three aircraft. My ticket shows "Airline Transport Pilot: DC-9, B-757, B-767 (the 777 came just after I retired). The system is comprised of the autopilot, autothrottles, autobrakes, flight director, RNAV and VNAV. All of these components are part of a larger bundle of 'magic' called the Flight Management System.

"The autopilot is pretty much the same as it has always been, just refined and refined. However, there are three separate autopilot systems that automatically engage in the approach mode to give redundancy. The autopilot may be used without any of the other autoflight components (and are the same as in a DC-6 or DC-9 plus or minus some details). The only restriction is that it cannot be used by itself without these other components below 1000 feet agl.

"The auto throttle system is used most all of the time and is turned on/off by a switch on the glareshield. It sets the power for takeoff, will maintain a selected airspeed or mach number and is somehow (magic again) connected to the Flight Management System so that it will maintain a cruise airspeed/mach number that is the most efficient for that flight segment. The autobrakes must be used for takeoff (procedure) and are selected by a switch. They will apply maximum braking to all wheels if the throttles are manually retarded to idle for a rejected or aborted takeoff. They may be used for any landing, visual or instrument, but must be used for a Category III approach/landing. The flight director (2 separate units, one for the captain and one for the first officer) is a standard dual-cue system (orange bars superimposed on the attitude gyro called the ADI or Attitude Directional Indicator) which may be used alone (hand flying) or coupled with the autopilot. It can be controlled manually by entering the desired heading and vertical command (altitude hold, selected vertical speed or go-around mode). It can be used in conjunction with the autopilot and/or the RNAVand VNAV.

"RNAV is the horizontal navigation system which is based on position information automatically gained from the DME (Distance Measuring Equipment), from two separate VORs (omnirange), and is backed up by three INS units (which become primary when out of range of VOR i.e., ocean crossing). This information is displayed in the cockpit on the HSI (Horizontal Situation Indicator)." (Author's Note. I am guessing that INS stands for Inertial Navigation System.)

"Flight plan information for RNAV and VNAV (and the Flight Management System) is entered by the crew into the CDU (cockpit display system) which is a very small computer screen and keyboard located on the center console between the pilots. There are two of these units; one for the captain and one for the first officer. If memory serves me correctly, this system even has the capability to download all this flight plan data via an inter-link with the company's flight control (dispatchers), thus not requiring a manual entry by the crew." (This paragraph is condensed from a clarification dated 02/18/2002 by Robert E. Mitchell.)

"The Flight Management System recognizes airways, ATC charted fixes, airports, etc. When engaged, it will provide heading information to the autopilot and flight directors, and fly the entire flight from the departure point (including any published instrument departure) to the initial approach fix at your destination. You can program it to fly direct from fix to fix or fly an entire airway route, ie: J22 to DCA, J14 JFK direct BOS. (Author's Note: From memory, DCA is Washington National, now Reagan, JFK is Kennedy, formerly Idlewild, and BOS is Boston, for Logan Airport.) You can change anything enroute at any time if you so desire. RNAV does not know anything about altitude. If you only engage RNAV, then altitude management is strictly the pilots' responsibility."

"VNAV (vertical navigation) is the altitude portion of the system. You must enter the desired cruise altitude and the altitude at which you want to be at the initial approach fix (it even has the capability to put you over the runway threshold at 50'...but that isn't used). When programmed, VNAV is usually engaged at 1000 feet agl. Along with the autoflight system it will climb the aircraft to the selected cruise altitude, level off, and retard the throttles to the selected cruise power setting. At the descent point (computed from the altitude at which you wish to cross a specified point) it will again retard the throttles and begin the descent, keeping you informed all along as to how the descent profile is coming along. There are however, safeguards to ensure that you do not climb or descend without proper clearance."

"In the approach mode, the autoflight system uses ground based ILS systems just as it has for years. In very bad weather conditions however things change a lot. All major airports now have instrument runways which have been designated as Category III runways. These ILS units and runways must meet a much higher standard and must have a lot of additional components."

"Category III is further broken down into Cat IIIa and IIIb and the above rules likewise apply. In both Cat IIIa and b, ceiling is of no concern, only runway visual range RVR (as measured along side the runway) is controlling and in the case of IIIb it can be as low as 300 feet! The crew and aircraft must be qualified for Cat III and the aircraft must be coupled to the autopilot, flight directors, autothrottle and autobrakes. It is a completely hands-off approach and landing. The only physical movements the pilot must make is to properly program the approach, lower the gear and flaps, arm the auto spoilers and reverse the engines after touch down. There is no requirement to see anything! You just hope and pray that all those little electrodes are getting the right signals and when you stop you're on the runway and not off in the grass somewhere. The aircraft will flare, touchdown, throttles retard to idle, the nose wheel settles on the runway, the brakes apply and centerline guidance rolls the aircraft to a stop! As I mentioned, the pilot may see a few of the green centerline light as the aircraft rolls out, but that is not a requirement. The hard part now is taxiing to the terminal. I must admit that it took quite awhile to completely trust the system and even then it was not a very comfortable situation. One other requirement: max crosswind component to initiate a Cat III approach is 10 knots."

"I realize that this is a quick, down and dirty description and I hope it helps. You would not believe the problems we had in training with 50+ year old 727 captains who had not been trained on a new aircraft in 10 - 15 years and the word computer scared them to death! It was a giant step! The young guys who had seen all this magic in the military in some form or another had no problem at all. Would you believe that the Navy now has full autoland to come aboard the carriers!

"As for me, I entered pre-flight in the fall of 1958 and spent 8 years in the Navy flying S-2s and A4s. My last year I was an instructor in an instrument flight training unit. I went with Delta in August 1966 and retired in 1997. I flew the DC-6/7, Convair 880, DC-9, DC-8, B-727, B-757 and 767 and the767ER. I spent 5 years (1986-1991) as an instructor in the Flight Training Department on the 757/767which was treated as one aircraft. My last year there I was a senior instructor charged with training new instructors. The last six years were on the ER flying to Europe. I was based in Atlanta all 31years.

Robert E. Mitchell

15450 Thorntree Run

Alpharetta, GA 30004"

Captain Mitchell's words inform me that the military pilot/commercial pilot dialogue of 1949 on the merits of GCA versus ILS would find no parallel in 1999. The passive electronic ground systems of 1999 owe their heritage to ILS. The military pilot of 1999 and the commercial pilot of 1999 would be talking about variants in packaging the electronic components but would have no issue about what the components accomplished and what the pilot relationship to them was.

The following remarks are based on several telephone conversations with Frank Davis, recently retired United Airlines pilot. The key upcoming phrase is "one green light" and its basis was the line of green lights down the centerline of an instrument-equipped runway introduced to this story by Captain Mitchell. These two veteran pilots do not know each other and had no communication other than reading what I have quoted from separate discussions with them.

United Airlines Captain Frank Davis retired from that airline in September of 2001. His final years with United were spent flying overseas in the Boeing 777. He served at various periods as a flight instructor in Boeing 727, 757 and 767 type aircraft and during other periods as a ground instructor in United's extensive family of aircraft simulation devices. In one conversation with him, Davis commented on the close "family" ties of the Boeing 757,767 and 777 aircraft, while also noting that the 777 actually incorporates systems to make automatic inflight broadcasts of aircraft performance data back to United's ground maintenance facilities. In an overnite stop at Denver in one Boeing 777, Captain Davis came back out to fly the same aircraft the next morning. He discovered that one engine had been replaced overnite. He was concerned enough to call his San Francisco maintenance base before taking the plane out again, questioning them on how the decision to change an engine had come up when the flight crew of the evening before had found no fault with the powerplant. He was assured that there was no outstanding problem with that engine but that data transmitted to the ground station informed them that the engine was nearing its hours of operation limit. The ground supervisor explained that United had the skills and the spare engine available at Denver and wanted to anticipate the support routine while the opportunity presented itself.

Boeing has scored with the pilots who fly this late 20th century series of aircraft. Even though competition with Airbus Industries has been fierce, and every fraction of a gallon of fuel was counted in range and efficiency calculations, the electronic package in the 'seven-five, seven-six, seven-seven' aircraft counted heavily in its acceptance. The procurement decision came down not just with airline management concurrence but with the crucial acceptance by the airline pilots who would fly the Boeings. The instrument flight package was a factor in its acceptance.

A Texas A&M graduate, Frank Davis began his flight career with the Air Force at primary flight school in Lubbock, Texas. He flew and appreciated the value of GCA instrument approaches in 1964. He made ILS part of his capability in 1967. While admiring fully the merits of these two methods of getting a plane safely back on the ground in instrument flight conditions, when there was a choice pilot Davis ultimately preferred ILS.

An airline pilot repeats flight profiles, from a take off at one regularly visited airport, then along a familiar enroute path to a landing at another regularly visited airport. This repetition of a given point-to-point experience occurs many more times than with the military pilot. Does the airline pilot become bored? Definitely not! Experience tells him or her that each flight segment, repeated in identical symbols many times on the traveler's departure and arrival screens, is always different, notwithstanding the repetitiveness on the flight display boards.

Let me use a personal, non-flight, analogy. My family lived in the Mission Hills section of San Diego, California, for three years and I had the rare-in-life opportunity to walk to my technology job down the hill to a business area called Five Points. It was just a two-mile walk. San Diego is called the city of the short thermometer. As a born easterner, I had always heard the criticism of California that there were no "seasons." Despite the compelling seacape of Coronado Bay in my broad view each morning, I became attuned to the daily changes in the beautiful foliage in my short gaze, and the wondrous changes in that seascape in my long gaze. An airline pilot flying the exact same point-to-point segments sees comparable subtle changes every time he or she flies. That not only takes boredom out of the job, it regenerates diligence in the application of the human senses to the job at hand, safe flight.

Frank Davis makes clear his love of flying. When conditions were VFR, he would often hand fly his aircraft to an assigned cruise altitude of say 39,000 feet, and then shift to autopilot. For descent, again providing conditions were right, he would switch out of autopilot and enter the let down phase. When the flight plan is a short segment, most often congested with aircraft, with conditions mostly IFR and therefore even more congested at destination, Frank Davis notes that the autopilot is hooked up at 1000 feet above ground level after takeoff. This is not the lazy way. The pilots have learned that it is the best way. It reduces pilot workload and lets the flight crew focus on seeing and hearing the seemingly minor detail that makes this flight just slightly different from the last time over this route.

Each airline has its own standard procedures. Davis calls this "the company way" to perform to plan. But, Davis emphasizes that the Captain of the aircraft is in ultimate command and when there is a situation not foreseen specifically in the flight plan and in the airline's page-heavy procedure manuals, the Captain takes charge and does it "his way."

When a destination airport is Category III, meaning equipped for no measurable ceiling and just 300 feet of Runway Visibility Range ahead, the airline Captain is in a role defined for the command pilot of an aircraft, a decision role. With a heavy repetition of "almost the same" prior situations to guide him or her, the human pilot elects to use the autopilot to effect the approach and landing. The Captain has been intellectually persuaded, with experiences repeated enough times to become "reliable data," that the autopilot provides a better way to execute descent, flare-out, and touchdown than the flesh and blood pilot could consistently manage. In this sequence, the cockpit crew can monitor the descent and landing profile and more alertly detect exceptions that might require intervention, such as loss of thrust from an engine.

There are other exceptions. There are always exceptions. For example, if a frontal passage and a possible wind shift might find the landing aircraft exposed to a severe crosswind, the Captain would elect to land the plane himself. This might also involve not just that physical intervention but a second intellectual one. For such a landing, the pilot would insist on better field ceiling and visibility conditions than Category III and if not available at the destination airport, would elect to take the plane to an alternate airport.

After a long airborne segment with a full load of Boeing 777 passengers to Frankfurt, Germany, Captain Davis put the full repertoire of his modern instrumented aircraft to work. It was a Category III landing. On the rollout, the flight deck crew could see just one of those green runway lights in the row of centerline lights. A "follow-me vehicle" was sent out to help direct the aircraft to the terminal. This former military pilot would declare, "mission accomplished."

It is interesting that Charles Lindbergh was most often referred to as Colonel Lindbergh. Ask for a show of hands at an annual convention of the Airline Pilot's Association from those who have flown in military service. Or put the question to a meeting of air controllers. Both queries would result in a strong showing of hands from those with military backgrounds. Those who made it with military training would applaud those who made it with all civil training. The feeling would be mutual. That connection has made for strength and it is unique in the landscape of professions in the United States.

The global acceptance of aviation and its rarely noted but irreplaceable round-the-clock performance are testimony to the achievement of pilots, technicians, flight attendants, engineers, aircrews, businessmen and the aerospace industry; our country can be justly proud of its part in establishing that record.

August 10, 2013: This page on this website has been among the most accessed pages. Deservedly so, as contributors have provided large portions of the substance. My only contribution has been to get the juices flowing. And in my small contribution, I have managed to make at least one big mistake. I am thankful for the next contribution. Instrument flying is one pursuit that that has a cruel reward for mistakes. With that, here is a contribution made in an e-mail to me in early August of 2013.

"Dear Mr. Dailey

"I came across your website today while research ILS SCS-51. I collect historical aviation instruments from 1940-1960's. I have a SCS-51 Glidepath Indicator and was interested in learning more about how they were used.

"I've acquired a Pilots Information Manual (PIF) from an ex WW2 pilot. It contains a page marked REVISED September 1, 1944, and it describes the operation of the SCS-51.

"On your website page http://www.daileyint.com/flying/flywar15.htm , it is stated:

"There was no SCS-51 in those war years, military or civilian."

"So I'm confused and would like to know your thoughts on this. Please regard my inquiry as a search for objective information, I mean no disrespect. I'm happy to send a pdf copy of the page from the PIF if you would like to see it. It also refers to Technical Order 30-100F-1 for complete instructions of the SCS-51 System, which I will now try to hunt down.

"I'm glad that I was doing this search because I now know about your book, which I will buy at Amazon. Thanks!

John Turanin"

Home | Joining the War at Sea | The Triumph of Instrument Flight