-------

.

Read The Triumph of Instrument Flight

- Navy Aerial Reconnaissance

- Warships at Morocco-1942

- Aircraft Carriers for Torch

- Battle for Morocco

- Bridging World Wars

- Supply and Support

- Husky, Palermo, Messina

- Bloody Salerno

- Luftwaffe Standoff Weapons

- Aircraft of World War II-"friendlies"

- Long "slog" at Anzio

- USS West Point AP23 War Cruise-part 1

- USS West Point AP23 War Cruise-part 2

- Singapore, Fateful Stop on "Joan's Journey"

- Update West Point

- Part I, Briggs on Casablanca, Sicily

- Part II, Briggs on Anzio

Cargo, troop ships in World War II. Many aircraft delivered themselves. P-39 Aircobras and P-63 Kingcobras to the Soviets featured here.

Copyright 2011

(many photos from U.S. Navy WW 2 Recognition Training Slide Set)

USNS Spica T-AFS 9

My personal photo file from World War II did not include a good closeup photo of an AK (cargo) or AP (personnel-troops) commissioned U.S. Navy ship. but only shots of then in huge convoys too distant from my destroyer, the USS Edison (DD-439), to see detail. A third letter, the A as in APA, meant the ship was an 'attack' transpot but my experience was the use of APs and AP:As interchangeably. The Bureaucrats in Washington making up names could not fully envision the needs of war. AR was for Repair in Navy talk and AF was a 'reefer,' a refrigerator ship, and a type of ship p;rominent in these pages, was the USS Chemung, an AO, for 'oiler.'

The photo above was a chance picture I took from the walkway behind the Holiday Inn in Portsmouth, Virginia, after Y2K. I could not read her hull numbers or stern lettering. One can see from the clean lines and superstructure of this ship that it is a modern auxiliary ship. The ship above is part of the U.S. Navy's modern auxiliary fleet, likely built from the keel up for naval needs "USNS" is a ship designation that entered the lexicon after World War II.

T. J. Tropea of Ft. Meade, Maryland, 20755, on 11/29/2007, provided my first identification for the ship above, and a clarification as to where built. She was built in the UK and purchased to become USNS Spica T-AFS 9 for the U.S. Her British name was RFA Tarbatness. The class was named "Lyness" after the British name of the first in the series of three that the U.S. acquired. Tropea served in the first of these vessels, T-AFS 8, USNS Sirius, and there is a T-AFS 10, USNS Saturn, original British name RFA Stromness. Sirius is now in service as a training ship for Texas A&M, Spica is being deactivated too, and Saturn is due for inactivation in 2009. Tropea informed the author by e-mail that Spica above was immediately identified by him because of black boot strap on top of the smoke stack. Tropea was the first to report aboard Sirius in January 1981. When the 'Gulf War' occurred in the last decade of the 20th Century our country once again encountered lack of transport for supplies. Troops were now being transported by air. In my earlier generation, we had seen the attempt to put WW I 'hog islanders' back into service, and saw them sunk by U-boats. We built Liberty and Victory ships with names like SS Amelia Earhart and SS West P:oint. After that war there was an attempt again to put these ships into some kind of preservation, but, the futility of that and the lesson WW I put an end to it. So, if our country needs ships, they buy them because we have almost no Merchant Marine and no shipyards standing buy to build ships. C-5s and C-17 and even C-130 aircraft handle the troop transport needs.

Now, please resume my 2005 discourse, updated August 30, 2011, to include delivery of aircraft to the European fighting fronts as it was handled in World War I..

One feature of the merchantmen of World War II, to a sea novice like me, were kingposts. In fact, our recognition cues for such ships went "MKKFKM" or variations. Decoded, on fore to aft, the letters mean "Mast,Kingpost,Kingpost,Funnel,Kingpost,Mast." A kingpost would consist of a vertical member like a short mast, to which would be attached a boom that could be elevated or lowered but pivoted at its base on its mast, depending on cargo lift progress, and in the cruising mode, would be elevated to form the upper arm of the letter K. I see no kingposts in the modern auxiliary above. Those verticals rising from the ships sides, connected by a horizontal overhead member, likely relate to cargo handling. MFM for Mast, Funnel, Mast would still be relevant. Aft of the after mast is a helicopter landing platform. Underneath may be a hangar.

The most memorable auxiliary ship I can recall from World War II was the USS Vulcan. She was a repair ship and my association with her was when she was berthed alongside the breakwater at Mers El Kebir at Oran, Algeria. My ship, the destroyer Edison, was berthed in the space next to her, probably as many as 100 times during World War II when Vulcan was the support ship for ComDesMed or Commander Destroyers 8th Fleet. She had the lines of an ocean liner of that era, a good looking ship. Even at a distance one could see two 5"38 cal. guns and a Mk 37 Director mount up forward that told she had not likely been fitted out for passenger service. Once aboard, the cavernous machine shops and storage spaces told of her Navy connection. E-mail correspondents who served on her up until the 1990s were testimony to her length of commissioned service, over 50 years by my reckoning. The contours of merchantmen do not change radically from age to age. The USS Ancon and the USS Cristobal were trim liner-conversions of World War II to Task Force communications ships. The two, sisters ships, would pass for good looking ships in any age.

From about 1943, USS Vulcan, AR-5, is the backdrop for Kelly Hall and Joe Dwyer, USS Edison's (DD-439) Engineering Officer and Asst. Engineering. Officer l-r, respectively. Edison is 'airing bedding' and berthed near the USS Vulcan at Mers-el-Kebir, Oran, Algeria. (I shot rolls of Kodak 35mm Panatomic slide film in my Kodak 35 camera but did not have the rolls developed until many years later)

Getting troops and materiel to the battle scenes in World War II required more than warships. From the Maritime Commission and other sources, the Navy purchased, acquired, requisitioned, leased, took out of red lead fleets anchored in rivers, you name it, passenger liners (see USS West Point's nee SS America's thrilling first war cruise beginning at Halifax NS) and cargo vessels, and add commercial tankers to support the insatiable thirst for energy. Passenger liners could be converted to troopships and with some upper deck alterations, nests of landing craft could be cradled. These would often become APs or APAs. The USS Doyen, served in the war in the Pacific and was designated APA-1. (It is the Doyen's Recognition Slide Kit that readers see in these pages.)

Cargo ships were also obtained from maritime registry ship lines and their superstructure modified to hold even larger landing craft for long oversea transits. When Navy -ommissioned, these became AKs. Their hulls were suited for supplies that troops would need. As fast as Liberty ships could be built, and they reached a level of one launch a day, they joined the wartime merchant fleet. My destroyer, the USS Edison convoyed many a Liberty with aircraft fuselages, steam locomotives, or even motor torpedo boats lashed to the main deck. Liberty ships and the later Victory ships usually went port to port with cargo and in my experience were not used for direct amphibious landings. Liberty ships were used for ammunition ships right in the offshore landing zones and at Gela Beach at Sicily; the SS Robert Rowan, was hit by a German aircraft and multiple spectacular explosions followed. At Anzio, Liberty ships came right into the little port, dropped anchor, and lighters were used to offload them. German heavy artillery shells launched into the harbor made this a harrowing day for any Liberty ship crew. (Later in the war, as design and construction caught up, LSTs and LCTs for Landing Ship Tanks and Landing Craft Tanks began to take over some of the transport needs.)

This page of this series is simply my way of remembering the Joseph Hewes (she was AP-50), Tasker Bliss, Hugh L. Scott and Edward Rutledge, all of which were sunk in Fedhala Roads Nov. 11,12, 1942. I saw them all go down. I saw many other courageous troopships, supply ships, bulk cargo ships and tankers go down from submarine and aerial torpedoes, and from Luftwaffe standoff weapons. We'll see those weapons in a future page of this series. Two early transport friends, SS Awatea and SS Marnix VanSint Aldegonde, were "conventionally bombed" to the bottom of the Mediterranean.

The page , Husky, Palermo, Messina shown in the sequence of titles down the left side of each page in this folder, will bring readers to the battle for Sicily which began in July 1943. (the author can be seen in the History Channel series entitled "Patton 360:, episodes 1, 3, and 4)

Now, I will offer some views on World War II in which my two books, covers pictured at the top of the left column ,share common themes. But, I had not perceived that when I wrote the original drafts about five years apart. So, this next essay on war materiel in World War II, is original writing on that war that is simply not available in any one source of which I am aware. Air and Space Magazine helped add the next perspective.

A Short Essay on Delivery of War Materiel, specifically aircraft, to the European Fighting Fronts in WWII

Here, from page 154 of my book "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945,"

"According to Historian (Samuel Eliot) Morison, General Brehon Somervell, the U.S. supply chief, pointed out that the Straits of Sicily were still too dangerous for all but the most urgent convoys. He argued that gaining control of the Mediterranean sea lane gave unchallenged access to the Suez Canal, thus adding up to an equivalent of 225 freighters saved from the Cape of Good Hope route to India." In another page on this website, U-73's skipper related how the wolfpacks congregated where the sea lanes converged, and the Cape of Good Hope was a crtitical place where Allied supply convoys converged for passage to India, and where so many ships were torpedoed and sunk. Sicily was the answer, the Allies took Sicily, reopened the Suez Canal and Somervell's observation was validated. Let me note that India was a destination, and also a new point of departure, opening up access to China, and to the Soviet Union via Iran. Shortly here, we will discover what another author contributes to our knowledge of supply to the Soviets. Remember, the Allies had a shipborne route to support the Soviets via the Arctic run to Murmansk, but the losses sustained were so heavy that the route could not be justified if any other routing was possible.

"Supplies!" Our seaborne freighters carried locomotives and aircraft fuselages strapped down on their main decks. U-boat commanders would perk up when their periscopes disclosed such high priority targets for their torpedoes. My ship, for my months aboard, July 1942 to October 1944, convoyed many such vessels.All this by way of noting that an aircraft or a locomotive were elements in the supply chain. What if we simply flew the aircraft to the war front? We did, as I will shortly cover, but first let me just note that an aircraft flown to the war zone is just as much a 'supply' item as one lashed to the deck of a ship.

In my book, "The Triumph of Instrument Flight: A Retrospective in the Century of U.S. Aviation," I make a number of detailed and thrilling references to "Operation Bolero," the huge effort to fly U.S. warplanes from bases in the Maritimes , across the North Atlantic to Prestwick, Scotland. Bombers like the B-17s had the instrument flight capabilities and the range to make the trip. Sometimes these planes would also act as guide planes for two Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, one off each aft quarter of the guide plane. Since the latter had a shorter range, stops in Greenland and/or Iceland would be needed, depending on headwinds. There was a counterpart effort to fly planes to the European theatre via the South Atlantic. Florida, Panama, Brazil, Ascension Island, West Africa and England was a routing. This took a lot longer, but it was used extensively, especially for the Navy patrol planes being flown over to join in the ASW effort against U-boats in the Bay of Biscay; some Navy squadrons were also based in the Azores. These efforts, while exciting for flying enthusiasts, had as their essential thrust, movement of supply to the war zone.

Now, while the Cape of Good Hope, and then the Suez Canal sea routes got U.S. manufactured aircraft (over 2000) to the Soviets and to China on eastern fronts, the Atlantic flight routes got planes to the Allies fighting from the west. There are some flights, that made it all the way to the eastern front, Britain or North Africa, through the Mediterranean, and via Iran to the Soviets. These had their heroics too, but these were exceptions to the high density deliveries just discussed. It was the high density deliveries that sunk Germany and forced splitting their efforts across two intense fighting fronts. Of course, with Hitler's 'deal' with the Soviets, and then breaking the deal, that really set this up.

So, three high volume routes of supply to the European war Allies have been discussed. Ship routes delivering planes via the Cape of Good Hope and then via the Suez Canal, air routes across the North Atlantic, and an air route across the South Atlantic. This latter route was long, and took several stops, and was not thereby as intensive volume-wise as the other two routes.

There was a fourth route for planes. I should have suspected it, but did not know about it until reading Air and Space Magazine, pages 58-65, titled "Lieutenant Ivan Baranovsky's P-39." The photo at the bottom of the title page shows a muddy looking fighter plane, slightly immersed in a shallow gray Siberian lake, with one prop blade, grotesquely up and bent back. It was here that Lieutenant Baranovsky set her down, on ice at the time, and here in its cockpit were found the Lieutenant's remains. Author Tim Wright relates the date of the almost surely forced landing as Sept. 19, 1944, and date of discovery of the aircraft as a tomb, as 60 years later, in 2004. Baranovsky was on a Soviet air war mission out of Murmansk when he went down. His P-39Q is now back where it was built, not being restored, but cleaned up for viewing in a Museum. Engine experts found two pushrods piercing the cylinder enclosure and speculate (in the article) that bad lubricants brought the plane down. My speculation from flyng planes like the F8F Bearcat, is that perhaps the props had not been 'pulled through' before the Lieutenant started his engine and took off.

Bell Aircraft plants in Buffalo and Niagara Falls, NY, built almost 10,000 of the P-39 Aircrobras, and later many P-63 Kingcobras. The Army Air Corps failed to find a prime use for these aircraft, but the Soviets did, using them to attack and shoot down incoming Luftwaffe bombers. But, how to get them to the Soviet Union. I have outlined the routes for sea transport, but those routes were long, or were contested. Pilots, often lady pilots, flew these single engine planes to Great Falls, Montana, then to Fairbanks' Ladd Field, where the Soviet pilots took them over, for flights across Siberia to mother Russia. Another great photograph in the article shows a P-39 snowbound on a ramp at Nome, Alaska. Nome would be a logical first stop for the Soviet pilots 'getting the feel of a new aircraft' on the relatively short first leg from Fairbanks. For the U.S. part of the transport responsibilty, almost all were sent, one flight, one pilot at a time. Emergency fields were far apart for the U.S. delivering pilots, air traffic control was in its infancy, and the terrain from Montana across western Canada to Alaska was daunting. The Soviet pilots' options were even fewer, but they worked on a mode of one mother plane, like a U.S. B-25, with six P-39s following. Over 2300 of the Aircobras went to the Soviet Union along this route. The article is a 'must' read for those interested in aviation. It is a little chopped up because it is a long piece inserted into the back pages of the magazine. Likely a web version would not have those constraints. I heartily recommend reading the entire article, and that is a FIRST on this website. airspacemag.com is the web addrress. That is not a live link because I have not been there.

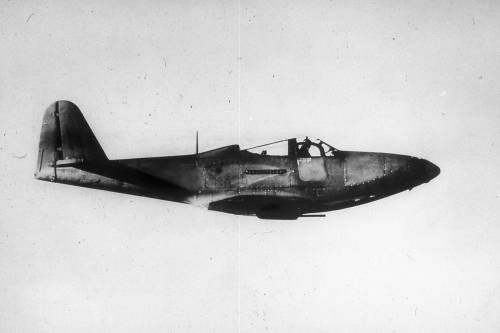

Above, Bell P-63 Kingcobra, successor to the Aircobra, from U.S. Navy Recognition Slide Set.

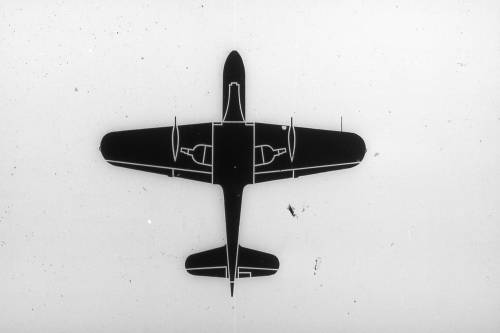

Above, a P-63 Bell Kingcobra, in a drawing, plan view, from the U.S. Navy WW II Recognition Slide Set

Above, the P-39 Bell Aircobra viewed from underneath; from the U.S. Navy WW II Recognition Slide Set

This closes the short essay on WW II and movement of supplies, specifically aircraft, to the war fronts of, mainly Europe. One can see that the P-63 Kingcobra was not just a slight makeover of the P-39 Aircobra.

----------------------------------------

The C-130 aircraft shown below dates from many years after World War II. It has been and is used for troop carrying, and gunship duties. It moves supplies. The United States buried its opponents with supplies in World War II. In a future conflict the United States will not have such a preponderant advantage and will seek to do more with less. Multipurposing will be one way to accomplish such an objective.

Lockheed C-130 has served many roles, including troop carrier and gunship

C-5s and C-17s now shuttle troops and vehicles to remote places. For the Gulf War, the nation tried to get available shipping into action for a major movement of troops and supplies to Kuwait. Saddam Hussein could read in the papers and watch television as one delay after another told the world that this was a poor way to prepare for battle. The U.S. no longer has available a ready source of shipping from maritime sources. The need to convey troops and materiel to a scene of action now demands fast reaction times.

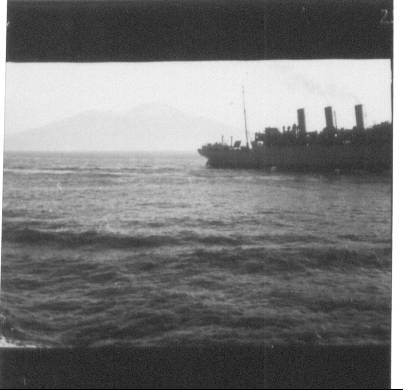

A WW II Merchantman with square stacks

The ship above is a passenger ship, put into WW II service to move troops from a port of embarkation to a port of debarkation. My destroyer, the Edison escorted this ship many times in World War II. We became attached to the ships we escorted frequently, both combatant and non-combatant. We rarely got non-combatant ship names or registry, and I did not obtain the name of this one. But I could never forget a ship with square stacks. I raced for my Kodak-35 camera and did not get all of her, but I got her stacks. If you look closely, the flat front face of the stack is in the sun. The 35mm 'positive' in my possession is marked, "Supreme Pan." I do not know if this vessel survived the war.

We depended on ships to get men and materiel to the battlefronts in WW II. We now need logistics that are much faster. There was one advantage to the earlier methods. While organizing and floating our convoys, one had time to think about what they were going to do.